I missed posting this in time for Oscar night, but rather than talk about Seth MacFarlane’s performance, let’s turn back the clock to another historic Oscar controversy…

Rhapsody Rabbit from ackatsis on Vimeo.

It was once lovingly called “The Great Controversy of 1946.” Two cartoons, by two different studios, with the same story and similar gags: a character’s piano recital is disturbing a mouse’s residency in the piano, set to Liszt’s “Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2.” One got the Oscar, the other wasn’t even nominated. How did this happen? Was it pure coincidence? Was it someone’s idea of a joke? Was there a genuine leak to the other studio?

Joe Adamson wrote diligently about the controversy over twenty years ago in his excellent book, Bugs Bunny: Fifty Years and Only One Grey Hare on pages 140-41:

Tex Avery was a witness when the folks at Technicolor, evidently stressed out, delivered one day’s Rhapsody Rabbit footage by mistake to the MGM cartoon unit, apparently confusing it with a disturbingly similar Tom & Jerry cartoon, on which Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera were then pinning their Academy Award hopes for 1947. When Bugs Bunny came up on the MGM screen, it was Hanna and Barbera who were disturbed first: pa reject much like theirs was apparently closer to completion over at Termite Terrace, and it was clearly going to be an Oscar contender for 1946. The Tom & Jerry cartoon, finally titled Cat Concerto, was rushed through the studio’s production process and put up for Academy consideration in the spring. That year’s crop of animated short-subject Oscar contenders was screened for the Academy, and then it was Friz Freleng’s turn to be disturbed.

“When they drew the rotation out of a hat,” [Freleng] remembers, “my cartoon was run after theirs, unfortunately for me. And the audience thought I stole from them. They got a nomination for it, and I didn’t. But I felt that was one of the outstanding things I had done. I enjoyed doing it.”

Further recollections are offered in this Animation Magazine article by Michael Mallory, quoting Joe Barbera:

“The idea of having the cat play the piano was fascinating to me. So we decided to go ahead with The Cat Concerto, and do the Second Hungarian Rhapsody. We happened to have under contract one of the best pianists in the United States at the time, a famous concert pianist. His name eludes me at the moment, but he loved doing it.”

[…]

“It was at a screening for the Oscar nominees. We [Cat Concerto] played first. When it came on, people were laughing like hell, and when the lights came on, Freleng was mad as hell. Then it [Rabbit Rhapsody] played, and the action was similar: Bugs walked up in the tailcoat, flipped it up, sat down, warmed up the hands, looking arrogant, all exactly the same. In ours, Tom, the cat, disturbs the mouse, and in his, Bugs, the rabbit, disturbs the mouse. Ours ended up as one of the five [Oscar] finalists, and people had the feeling that he [Freleng] was ripping off our cartoon, but he said, ‘No, no, no, I never saw your goddamned lousy cartoon!’”

“I really believe that [it was a coincidence]. Freleng had a sense of humor, we just thought the same, and our gags were the same.”

“[But…] What’s a rabbit doing with a mouse?”

Neither party seems to be accusing the other of plagiarism, although Barbera is certainly planting some amused skepticism by suggesting that Tom and Jerry are the more natural fit for this scenario. But the T&J cartoon’s concept is arguably just as absurd: why is Tom, who has been established as a house cat in all prior entries, suddenly performing at Carnegie Hall?

But arguing which cartoon is funnier/more original does not answer the question: was it plagiarism, or just a coincidence? I believe I can firmly establish it was the latter, beyond the fact that neither Freleng nor Barbera contested otherwise.

Adamson’s account also states that Terry Lind painted her backgrounds for Rhapsody Rabbit in April 1946, and that animation was well underway by that point. This is true, and it corroborates with the new documentation I and other historians have uncovered since Adamson’s book.

Peter Gimpel, Jakob’s son, provided interesting conjecture some eight years ago, but it falls apart given the fact that Shura Cherkassky was not the pianist of Cat Concerto.

In general, a classic Hollywood cartoon’s soundtrack was recorded after the animation had been completed or nearly completed. In certain cases, when the music dictates so much of the action, it would be recorded first. The dates procured from recording records at both studios reveal the following:

2 February 1946

Pianist Jakob Gimpel was recorded for Rhapsody Rabbit (and paid $250).

8 April 1946

Pianist Calvin Jackson was recorded for The Cat Concerto.

8 June 1946

Mel Blanc recorded his dialogue for Rhapsody Rabbit(and paid $125).

NOW ESTABLISHED AS FACT: Rhapsody Rabbit pre-existed Cat Concerto, and the former overlapped into the latter’s production timeline.

So did that Technicolor mix-up really happen? More than likely. Something absolutely happened because both cartoons were rushed, in different ways, giving credence to the story that both studios were aware of the other cartoon’s existence.

The evidence that Cat Concerto was physically rushed through production is staggering. For starters, the cartoon features animation by Irv Spence and Dick Bickenbach, both of whom were not at the studio until mid-1946. (Spence had returned from a stint at Jam Handy’s, Bickenbach had come over from Warners. Did Bickenbach give the idea for Cat Concerto to his new bosses? I’ve heard nothing of the sort, and there’s no proof, anecdotal or otherwise.)

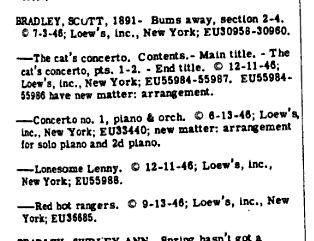

Furthermore, its production number of 165 indicates that it didn’t go into production until after The Invisible Mouse (163), a cartoon released in September 1947. That doesn’t make Cat Concerto‘s release of April 1947 seem too expedited. But unlike the other MGM cartoons, its musical score was copyrighted in sections, and far ahead of much earlier Tex Avery cartoons like Lonesome Lenny, Henpecked Hoboes (still under its working title Bums Away), and Red Hot Rangers, as evidenced here:

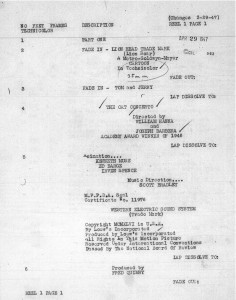

Also of considerable interest is Cat Concerto‘s copyright synopsis, with the note of “Changes 3-29-47,” indicating that the typist had viewed a print prior to this particular synopsis. March 29th was sixteen days after Jack Benny presented the Oscar to Cat Concerto. So as soon as it was released, it was touted as an Oscar winner in the opening titles, unlike cartoons that had that proclamation inserted into the credits well after the fact (like Yankee Doodle Mouse, Quiet, Please!, and Johann Mouse (though most surviving prints retain the original release titles); The Little Orphan was also always emblazoned with the Oscar stamp in its original release).

In the case of Rhapsody Rabbit, it was not rushed through production – it was pushed up the release schedule severely.

Had that not been the case, it would have likely sat on the shelf for another 15 months, and have its opening title music scored at a much later date (surviving records do not indicate when Rhapsody Rabbit‘s non-piano music was recorded). Its production number of 1040 suggests it would have been a late 1947 or early 1948 release, as it’s between Daffy Duck Slept Here (1039) and Nothing But the Tooth (1041).

What seems to have clearly happened is that Warners got wind of the accidental delivery to MGM, or at least were aware that MGM knew of their cartoon, and they pushed Rhapsody Rabbit up the backlog, swapping it with another (decidedly less ambitious) Bugs Bunny cartoon. My theory is that this cartoon was Chuck Jones’s A Feather in His Hare (production number 1023).

My reasoning? Mel Blanc recorded his lines as Bugs on June 2, 1945, and Mike Maltese recorded his dialogue as the Jewish Indian on November 17 later that year. The cartoon was not released until February 1948. That’s fairly jarring, even with all the complications of the Warner system.

Milt Franklyn’s orchestral scorings were generally recorded in production number order, with cartoons in the same number range scored the same day. The March 22, 1947 session is odd in this regard: Nothing But the Tooth (1041) was scored with A Feather in His Hare (1023). Therefore, I can offer no other explanation for this disparity other than the earlier cartoon was shoved down the assembly line, also explaining why no Bugs cartoons by Jones were released in the 1947 season.

MY CONCLUSION: I firmly believe that no one ripped off anybody and that the similarity is truly coincidental. Rhapsody Rabbit was pushed ahead on the release schedule after the majority of the work was done, while The Cat Concerto was physically rushed in nearly every department.

Piano recital cartoons were just a hot commodity that year. What isn’t brought up at all is how a third cartoon centered around this theme, with Woody Woodpecker and Andy Panda (and no mouse nor Franz Liszt), was also in the Best Cartoon of 1946 Oscar race. Musical Moments from Chopin, a Walter Lantz Musical Miniature directed by Dick Lundy, received the nomination that Rhapsody Rabbit didn’t, and was also screened for the Academy before it was released to the general public.

In hindsight, Freleng’s [justifiable] resentment seems to have less to do with the origins of the concept than the obvious Hollywood politics at play. There was always blatant ballot-stuffing at the Academy, given MGM’s many members and prestige in the industry, accounting for the cat and mouse’s seven wins (though it seems just as likely voters preferred the humbler H-B Tom & Jerrys to the more ambitious filmmakers like Freleng, Avery, Jones, Hubley, et. al.). There’s no doubt in my mind that the screening was rigged by MGM to make the Warner cartoon look like plagiarism. Afterwards, MGM began to try avoiding this kind of conflict by routinely getting what it felt was the best “Oscar bait” out to the public as soon as possible (though they found to their horror that Tom and Jerry in the Hollywood Bowl, a cartoon released a year earlier than it should have been, was nothing on Gerald McBoing Boing by the new kids in town).

It’s a shame both studios felt threatened by each other, because the controversy has cast an unnecessary cloud over two very fine pictures. But the research shows that this was one of those great Hollywood coincidences that was just that – a coincidence.

Considerable thanks to Keith Scott, David Gerstein, and Kurtis Findlay for their essential assistance.

Feb. 27, 2013 Update: Michael Barrier has posted a generous response, about where the influence for these cartoons may have likely come from. He also notes I may have pegged Dick Bickenbach and Irv Spence’s arrivals at MGM much later than they really happened. I confess, this is likely true. The first cartoon with Dick Bickenbach’s animation, A Mouse in the House, was in animation by January 1946, so he was certainly around by much earlier than “mid-1946”. Not exactly sure of Irv Spence’s return, though it was later.

Thank you for clearing up the controversy behind these two excellent cartoons, which are both favorites of mine. Now one can watch both of these films without coming to the conclusion that they were purposefully trying to plagiarize each other.

I finally bought and read all of your book in less than one day! Around 50-60% of the information in there, like the nitty gritty behind the scenes production stuff and which studio did what, I had literally no knowledge of. I also feel that you treated the various parties in your book fairly and objectively and pointed out the character flaws that people on both fronts had and why those were major factors in why Ren and Stimpy ended up the way it was, not to mention the amount of citations and quotations you added to back up your conclusions.

The whole fiasco reminds me of those infamous Buddy Rich bus tapes that apparently inspired Jerry Seinfeld and his show back in the 90s. Buddy was a perfectionist and expected the most out of the people he worked with, but could also be very harsh when the musicians weren’t living up to his standards or disrespected him, and even resorting to saying vulgar things as a form of discipline, mainly because the musicians he was chewing out were pretty young and inexperienced. Many bandleaders during the Swing Era had Rich’s attitude but weren’t quite as vocal about it. People who knew and worked with him closely have said favorable things about Buddy and how much of a genius he was.

Here is my review of Sick Little Monkeys if you’re interested in reading it. Obviously, I have said some of these things in comments I have left on other blogs and of course, the comment I left previously here, but here, I attempt to tie together all those thoughts with my overall impression of what you were trying to convey in your book. I hope you like it.

Note: I tried to submit this comment a few times in Firefox but it kept telling me I entered the wrong captcha response, so ignore those comments if you got them.

http://www.amazon.com/review/R2I4GWP8HX3GFZ/ref=cm_cr_pr_cmt?ie=UTF8&ASIN=1593932340&linkCode=&nodeID=&tag=#wasThisHelpful

The only good thing about the Oscars was William Shatner, and here’s why. Having Seth Macfarlane host it at least got those uptight mother fuckers to acknowledge the Science Fiction genre. (okay, it’s Star Trek, I know it’s been more love boat than sci-fi in the last 20 years, but Shatner represents when it was good..) Anyway, I can say this, plagiarism is wrong. As many people seem to have forgotten in this age. (no really, that’s true. Yes, It’s gotten to that point) As for these cartoons, it was obvious to me even as a kid, they were all ripping off each other. Even as a kid, this made me feel uneasy. Ideas don’t come from nowhere. I’m willing to bet once ripped off the other, though I can’t say for certain which.

Thad, I’m a little late to the party — I don’t spend a lot of time online, and only discovered your blog this week — but I’m just writing to add my congratulations to the many you’ve already received for this piece. VERY interesting stuff, some topnotch sleuthing, and I must say I really enjoyed it. Congratulations again!

Thanks, J.B.! It’s a pleasure to get kudos from such an accomplished historian as yourself. Loved the SNOW WHITE book, and I look forward to anything you write next.

Personally, I would have given the award to Woody Woodpecker. The premise does not seem as forced as the other two.

I often toyed with writing an article on the ‘performance’ cartoons, where a whole cartoon was devoted to the performance of one (or possibly as many as two) classical pieces. “Largo al Factotum” inspired Tex Avery, Bugs Bunny, Woody Woodpecker, and Heckle & Jekyll, for instance. It never occurred to me to wonder if anybody was swiping, or if it did I assumed everything flowed downhill, with Terry at the bottom and Lantz just above. Anyway, much enjoyed, and your detective work is truly impressive.

Just a note about the following comment: “In general, a classic Hollywood cartoon’s soundtrack was recorded after the animation had been completed or nearly completed. In certain cases, when the music dictates so much of the action, it would be recorded first.” This was definitely not so with my father’s work, nor Friz’s…they both recorded first and everything was timed to the 24th of a second (or 12th of a second) on bar sheets or exposure sheets which were marked with the recordings. No big deal…just sayin’…

Hi Linda,

Thanks for the correction, which I have posted. In general, I’ve seen documentation listing the orchestration as being recorded well after the animation was completed, for all of the directors’ cartoons, including both your father’s and Freleng’s. To cite one example, the music for Freleng’s PIZZICATO PUSSYCAT was not recorded until after the studio reopened in January 1954, well after substantial animation had been completed.

Could you possibly explain the difference between an orchestration recording after the animation was completed and what Jones or Freleng did with Carl Stalling, and recorded, before animation started? I’d greatly appreciate it and welcome anything that helps me understand the inner-workings of the Warner studio further. I also have to thank you for sharing your letters from your father, as they are absolutely illuminating.

My two cents, long after the fact–there is nothing suspicious about the similar premise, and who but a mouse is going to be living in a piano?

However, the gags are astoundingly similar–even the moment where the mouse encourages his rival to lapse into a contemporary musical idiom (A Boogie Woogie tune in Bugs’ case, The Atchison Topeka and the Santa Fe in Tom’s.) The timing is near-identical. The style is different, and one thing the best T&J’s always had going for them was a very solid sense of style. WB was more eclectic, as you’d expect with so many geniuses working in one place.

So yes, I believe the Technicolor story, and that Hanna and Barbara couldn’t resist taking with both hands–which we know animators of that era (and really, every era) did as a matter of course (I can’t be the only one who has noticed how many Pixar features were semi-plagiarized–and brilliantly so–Toy Story is clearly a retake on Jim Henson’s The Christmas Toy).

Freleng was angry not because of the borrowing but because people thought he’d been the borrower when he was in fact the borrowed from.

I like both cartoons, but Freleng’s is the best. And the Oscar proves nothing, as you only have to look at the best picture/actor/actress winners over the past near-century to know.