It’s difficult to fairly assess the overall output of Paul Terry’s studio. On one hand, they are certainly the foremost reminder that not every “classic cartoon” is a “classic”. Every aspect of a Terrytoon’s production is generally retrograde. Whereas even a blind man could tell the difference between a 1930s and 1940s cartoon at another studio, it’s rather difficult to make the same differentiation with a Terrytoon without looking at the copyright date.

Whereas what I see in the Famous Studios cartoons are guys who probably could’ve done something better under more favorable circumstances (before they all laid down and died because of the studio’s repetitious constitution), the Terry cartoons are largely the work of willful hacks. Willful hacks clearly having a good time making the cartoons, throwing anything at the wall to see what sticks and refusing to learn from their mistakes.

Paul Terry might have at least been as good a producer as Walter Lantz, who managed to produce decent, entertaining time-wasters in spite of having no aesthetic sense, if it weren’t for the studio lacking a solid story department. Cartoonist/historian Charlie Judkins has been working on a history of the Terrytoons for years, and has done some much needed research on what made the studio tick. It’s common knowledge that Paul Terry was the primary reason the cartoons bearing his name are largely weak, but solid fact is preferable to unsubstantiated blanket statements. I asked Charlie to shed some light on the Terrytoon story department’s mode of operation and here’s what he wrote:

John Foster was put in charge of the story department around 1938. The initial other writers working under him were Al Stahl, Don McKee, and Tommy Morrison. Izzy Klein joined around 1940 and stayed for about two years. Not sure how long Stahl and McKee lasted there. Of course, Paul Terry himself was active in the story department well through the 40s (and probably 50s) which is a big part of why the films are so weakly gagged. Terry forced the storymen to keep whatever he came up with, but he threw out lots of their gags. Foster retired around 1949, at which point it seems like Morrison took over leading the department. Howard Beckerman told me that when Foster retired he needed money, so Terry gave him a job transcribing jokes from popular radio shows to steal. Terry also had a man he paid and sent to NYC once a month to go see whatever the latest “A” cartoon (WB, MGM, Lantz etc.) was and write down gags that Terry could steal. So it seems like there was a lot of repurposed material being used at the Terry studio.

The studio hierarchy may have differed greatly from the Hollywood shops at Fleischer/Famous, but authorial touches were still discernible. Watchful eyes can determine who was responsible for tighter direction (Willard Bowsky, Bill Tytla), superior animation (the Dave Tendlar and Tom Johnson units), or sharper stories (Irv Spector) in the Fleischer/Famous product. Comparatively, it’s inscrutable to determine who was responsible for the success or failure of a Terrytoon because the directorial and writing duties were even more haphazard. It’s therefore impossible to determine why the Heckle & Jeckle series was regularly very funny while the other Terrytoons are all over the map, other than they just are. Further research may not make the films any better, but it’s still direly needed.

This little oddity is one of those Terrytoons that begs viewers not to thoroughly dismiss the studio at face value. The Lyin’ Lion is one of the few decently written and staged Terrytoons of the late 1940s. The NY writers were obviously far more enamored with Bert Lahr, and specifically his performance in The Wizard of Oz, than the Hollywood writers were. Looey the Great shows up in many Terrytoons throughout the decade, and Sid Raymond did an approximation of Lahr’s voice for the Wolfie character at Famous.

This was also among the earliest Terrytoons to feature the work of Jim Tyer. He animated almost the entire first minute-and-a-half, and one of his scenes has what is inarguably some of the most intriguing direction in a Terrytoon. It’s the single scene from 1:27-1:43.

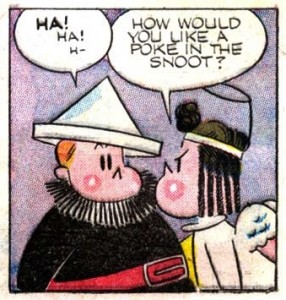

There is a lot going on in this scene and Tyer gets it all across perfectly. One thing that makes Tyer’s work compelling is that along with pulling no punches in his craziness, he was able to do it without compromising the acting. Looey is adamant that he’s a brilliant circus performer, conceitedly and clumsily trying to climb the ringmaster’s head for his outrageously asinine act. The ringmaster is thoroughly exasperated that the has-been hasn’t retired and is clearly mortified at being a part of this disaster.

Tyer emphasizes the ringmaster’s frustration in a most wonderfully cartoonish way: by zooming in on his distorted face while Looey is still trying to climb to the top. This shot is actually three different scenes stitched together almost seamlessly to look like one continuous truck-in/truck-out shot. I’ve slowed the scene down to a quarter of its original speed in this video.

Though a landfill the Terrytoon output may be, inspired moments like this are nonexistent in most animated shorts of the last half-century. Their presence at least moves the studio to an echelon a little higher than bottom-of-the-barrel in the whole oeuvre of twentieth century cartooning.