Being one of the most original and influential visionaries of all-time has nothing to do with being a decent human being. A harsh truth anyone interested in the arts has to accept straightaway. And in the entire history of cartooning, no one quite illustrates this principle like Al Capp.

Being one of the most original and influential visionaries of all-time has nothing to do with being a decent human being. A harsh truth anyone interested in the arts has to accept straightaway. And in the entire history of cartooning, no one quite illustrates this principle like Al Capp.

The short version: Li’l Abner had no equal in the medium of comic strips in its 1.5 decade prime (arbitrarily beginning any year in the latter half of the ’30s and ending in the early ’50s) and the man rose to the status of celebrity like no other cartoonist of that era. The strip’s biting narrative and rich draftsmanship had a major impact on Walt Kelly, Harvey Kurtzman, Charles Schulz, and any print cartooning visionary to emerge after its creation. Only Kelly’s Pogo managed to match (and, arguably, surpass) Capp’s Dickensian-like skill of enhancing the mundane, creating compelling characters out of even the incidentals. Whereas Kelly’s own sympathies were always with his characters, Capp held his characters in open contempt; the joy Capp got out of his self-aware style was exposing what unlikable, disdainful creatures every single one of his creations were.

Unfortunately, that cynical bile, as it so often is with the best talents, was inseparable from the work and the actual person. Capp’s gift for storytelling expanded to his personal and professional life, and he often spun fabricated stories that would be funnier if they weren’t at the personal expense of so many other people in a less than opportune position to defend themselves. His early losses, both physically (he lost his leg in a streetcar accident when he was nine) and creatively (he never finished art school and Joe Palooka’s Ham Fisher severly mistreated him), only fueled his abusive nature rather than enlighten him.

He was abusive to his friends, business partners, collaborators,and family; a misogynist who mistreated his wife and lovers with equal disdain; and, to borrow from Mark Evanier, a serial rapist whose third-leg antics (which victimized everyone from the nameless to Grace Kelly, Edie Adams, and Goldie Hawn) were defended by no less than Richard Nixon. If there is a positive side to this grisly story, it’s that Capp undoubtedly did feel remorse and disgust for the pain he caused. Suffice to say, it’s a dark, tragic, and, at times, humorous story worth telling with utmost delicacy.

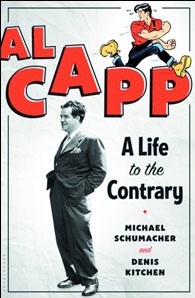

Michael Schumacher is no stranger to chronicling the life of a widely influential cartoonist, and no one has done more to champion Al Capp’s Li’l Abner than Denis Kitchen has with his excellent reprint collections. As a team, they’re more than qualified to chronicle the life of the man behind Dogpatch, and Al Capp: A Life to the Contrary more than meets the goal of being a standard biography. If you are worried that aspects of the man Capp will be whitewashed, don’t be. This is the whole bitter story.

Some of the book’s chronology jumps around a bit much for a biography (the authors talk about the latter half of the ’40s in one section, and then discuss World War II in the next), and an analysis of why exactly Li’l Abner is the comic masterwork that it is, rather than simply stating that it is, would have been welcome. But given the scope of this book, and the gripping life story they have to tell in some 260 pages, they are admirably thorough and pull no punches. This is the biography David Michaelis wishes he wrote, one that doesn’t require penning a fantasy version as his atrocity Schulz and Peanuts did.

Do not base your opinion of Al Capp on that isolated YouTube clip of his encounter with John Lennon and Yoko Ono that is constantly making its rounds in social media. Schumacher and Kitchen have presented the real Al Capp here in their pageturner: admirably creative, but there’s not much to admire otherwise. Though in all fairness, that clip does rather accurately depict why anyone today can hear a Beatles song and know exactly what it is, but remain dumbfounded if they actually encounter a Li’l Abner strip. Sad, ain’t it?

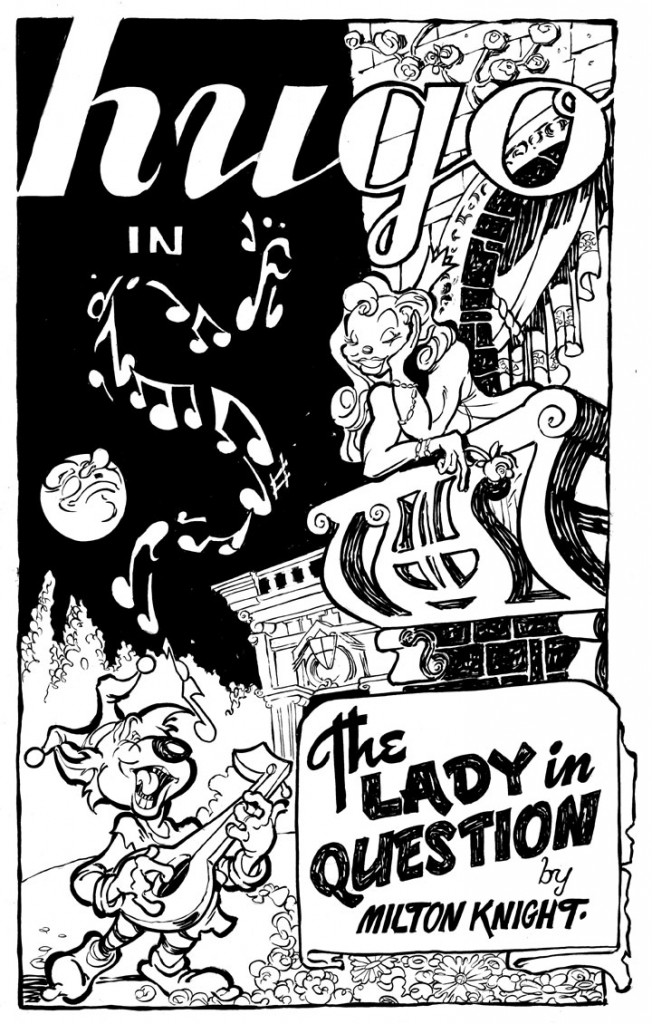

I’ve had absolutely engaging conversations with artists whose work I’d quite like to forget. Then there are those whose work I’ve always admired (and always will) whom I wish I never had a dialogue with at all. The cartoonist and animator Milton Knight fits neither category. I always learn a great deal from my chats with him and from looking at his art – and furthermore, I always enjoy it.

I’ve had absolutely engaging conversations with artists whose work I’d quite like to forget. Then there are those whose work I’ve always admired (and always will) whom I wish I never had a dialogue with at all. The cartoonist and animator Milton Knight fits neither category. I always learn a great deal from my chats with him and from looking at his art – and furthermore, I always enjoy it.

The scrapping of the cartoon did not hinder Freberg’s productivity. Even before FDR’s demise, Clampett had cast him for one of the titular Goofy Gophers (one of the director’s last projects for the studio). Chuck Jones had also used him for Bertie in Roughly Squeaking and he voiced Grover Groundhog in One Meat Brawl for Bob McKimson.

The scrapping of the cartoon did not hinder Freberg’s productivity. Even before FDR’s demise, Clampett had cast him for one of the titular Goofy Gophers (one of the director’s last projects for the studio). Chuck Jones had also used him for Bertie in Roughly Squeaking and he voiced Grover Groundhog in One Meat Brawl for Bob McKimson. Clampett never directed at Screen Gems, where he might have made an actual difference. He only wrote his own stories and gave his input to others. He was also responsible for getting Stan Freberg over to do voices at the studio (as well as Dave Barry). Freberg is heard in numerous Screen Gems cartoons of the period, such as Boston Beanie and Wacky Quacky – both trainwrecks that bely any description beyond “a schizoid’s point of view.”

Clampett never directed at Screen Gems, where he might have made an actual difference. He only wrote his own stories and gave his input to others. He was also responsible for getting Stan Freberg over to do voices at the studio (as well as Dave Barry). Freberg is heard in numerous Screen Gems cartoons of the period, such as Boston Beanie and Wacky Quacky – both trainwrecks that bely any description beyond “a schizoid’s point of view.” You will note that Freberg is directed very differently in these two cartoons. In the Warner cartoon, Freberg is doing a more subdued, menacing Lorre, as seen and heard in a film like Mad Love (in which Lorre does play a mad doctor). In the Columbia cartoon, Freberg is directed far ‘cartoonier,’ akin to Lorre’s much less serious roles in films like Arsenic and Old Lace.

You will note that Freberg is directed very differently in these two cartoons. In the Warner cartoon, Freberg is doing a more subdued, menacing Lorre, as seen and heard in a film like Mad Love (in which Lorre does play a mad doctor). In the Columbia cartoon, Freberg is directed far ‘cartoonier,’ akin to Lorre’s much less serious roles in films like Arsenic and Old Lace.