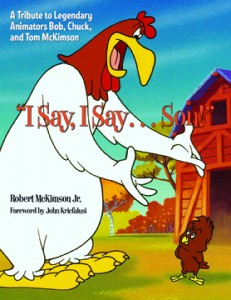

In the other corner of animation history, there have been many books about the Warner Bros. cartoons as a whole, but few bely the term “vacuous”, and even fewer examine individual figures. Certainly a book about Robert McKimson, a key player in the Termite Terrace legacy, has never been considered, which is why I Say, I Say … Son! : A Tribute to Legendary Animators Bob, Chuck, and Tom McKimson is sparking curiosity. Penned by Robert McKimson, Jr., the book “details how his father Bob McKimson created such beloved characters as Foghorn Leghorn, the Tasmanian Devil, Sylvester Jr., and the original Speedy Gonzales, and explores Chuck and Tom McKimson’s voluminous body of work at Warner Bros. Cartoons, Dell Comics, and Golden Books.” (From the press release sent out by Santa Monica Press.)

In the other corner of animation history, there have been many books about the Warner Bros. cartoons as a whole, but few bely the term “vacuous”, and even fewer examine individual figures. Certainly a book about Robert McKimson, a key player in the Termite Terrace legacy, has never been considered, which is why I Say, I Say … Son! : A Tribute to Legendary Animators Bob, Chuck, and Tom McKimson is sparking curiosity. Penned by Robert McKimson, Jr., the book “details how his father Bob McKimson created such beloved characters as Foghorn Leghorn, the Tasmanian Devil, Sylvester Jr., and the original Speedy Gonzales, and explores Chuck and Tom McKimson’s voluminous body of work at Warner Bros. Cartoons, Dell Comics, and Golden Books.” (From the press release sent out by Santa Monica Press.)

The book features a foreword by John Kricfalusi and an introduction by Darrell Van Citters. Kricfalusi’s is, of course, more anecdotal than anything else but still entertaining, and Van Citters delivers a curt, satisfying explanation of Bob McKimson’s importance in Warner animation. (Although he is incorrect to say McKimson “often animat[ed] substantial portions of his films.” It wasn’t “often”, only in the severe circumstance of McKimson’s unit getting laid off in the first half of 1953 before he was. He animated all of The Hole Idea by himself, as well as the majority of Dime to Retire and Too Hop to Handle; the latter two had animation by Jones animator Keith Darling.)

If only the actual, first-person text expressed a similar combination of John K.’s enthusiasm and Van Citters’s authority. While Robert McKimson, Jr.’s writing contains no substantial errors to my knowledge, keen insight into what made his father tick as an artist or director is alarmingly absent. Rather, it’s largely a potpourri of “fun facts” that almost every serious student of the Warner cartoons already knows from just watching the films. Quite a lot of the information is ostensibly based on Michael Barrier’s 1971 interview, and the wording and sentence placement is often random.

There are hints at where this book could have gone with the biographical information McKimson provides. The McKimson brothers’ father, Charles Sr., encouraged them to pick a career very early and develop work ethic, regardless of whether they chose a different vocation later. It obviously made a life-lasting impression on the artists. Robert and Tom McKimson were among the few Warner alumni who received formal art education before they got into animation. On their first day at Harman-Ising, Robert and Tom arrived at their desks precisely at 8 o’clock and proceeded turning out more footage than anyone else at the studio. “Consummate professional,” that oh-so-archaic endorsement, applied to all three of the McKimson artists from the very beginning, and I think that outlook shaped their artistic styles, particularly Robert’s, in a way that’s fascinating enough for a formal telling.

Robert McKimson was, self-admittedly, also a sort of pawn in studio politics; a candidate for director, like Art Davis, that Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng encouraged so there would be a less emotional personality in the studio intelligentsia. When Warners resumed normal operations in January 1954, all of Jones and Freleng’s crew eventually returned, and McKimson’s did not. McKimson’s wife also predeceased him by more than a decade as he continued to direct, and he “never quite got over it,” as his son writes. These events are certainly demoralizing to any working person, and a careful examination might have painted a more intimate portrait of a seldom discussed talent.

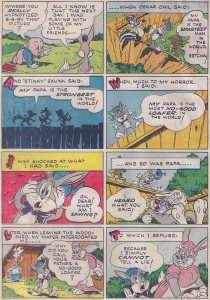

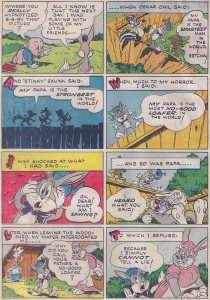

From Looney Tunes & Merrie Melodies Comics #41, March 1945. Drawn and inked by Tom McKimson.

The text is also surprisingly lacking regarding the other brothers. Chuck McKimson is almost entirely absent from the book. Certainly none of his work for Pacific Title is included, which was specifically mentioned in advertisement for the release. The coverage of Tom McKimson’s work for Western Publishing is too sweeping and focuses almost exclusively on his drawings for children’s story and coloring books. As we’re reminded, Tom McKimson had enormous responsibility as Western’s art director beginning in 1948, but we’re given no indication of what his working relationships with the other (and in some cases, far more important) artists were like. It’s also a pity David Gerstein or I weren’t consulted, as I would have been happy to provide comic book scans of several beautiful covers and choice pages that Tom illustrated (including non-Warner characters). As a result, the inclusion of Chuck and Tom McKimson seem to be almost afterthoughts to the larger story of Bob McKimson’s work.

It is an art book, so what matters largely is the art, and if it warrants the higher price tag such tomes demand. Is it good and is the art presented well? The answer is largely yes. A few drawings were obviously sourced from low-resolution scans (hence heavy pixilation), but that hardly matters when there are hundreds perfectly illustrated.

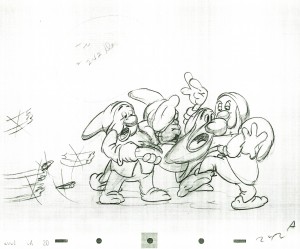

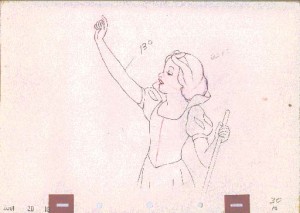

I learned and reflected more just by gleaming at the original vintage artwork than I did from the writing. Art for a proposed children’s book entitled Mouse Tales shows that Tom and Robert McKimson had the Disney style down peg before the studio did (and by association, they established the Harman-Ising studio’s style before it even existed). The tale of the ill-fated Romer Grey Binko cartoons is recounted with appropriate briskness and enticing drawings.

While the 1930s Schlesinger work by the McKimsons is all but unrepresented, fans of the glory Warner years need not worry. There are some great layout, animation, and model drawings from Robert and Tom McKimson’s years with Bob Clampett, emphasizing their role as significant foundation for those important films.

Robert McKimson’s tenure as a Warner director is the period represented heaviest by vintage art, including his infamous layouts that a great many of his animators reportedly found insufferable. (A whole scene from Of Rice and Hen is reproduced.) The key difference between McKimson’s methods and Jones’s as a director-character layout artist is that while both of their three-hundred drawings per cartoon are technically perfect for animation, McKimson’s simply aren’t expressive for filmmaking purposes the way Jones’s are. They discourage the kind of interplay and the proclivity for acting Jones’s animators enjoyed, the same kind Clampett encouraged when he was directing both McKimson and Rod Scribner. When the studio reopened, McKimson’s cartoons were populated by largely incompetents (save Warren Batchelder, a former assistant to Virgil Ross) who had no choice but to follow the layouts strictly as given to them. It cost McKimson’s last decade of directing at Warners any rambunctiousness, but at least it spared a Scribner, Emery Hawkins, Bill Melendez, or Manny Gould from getting stifled.

A scene from Fool Coverage, released in 1952. Robert McKimson layout left (scan from the McKimson book), finished scene from the film (obviously by Rod Scribner) right.

The book is heavily illustrated with a lot of “Limited Edition” art either drawn by the McKimson brothers, based on their original drawings, or recreations of scenes from the McKimson-directed Warner shorts by other artists. This isn’t as problematic as it sounds, because unlike the Freleng studio art (gangly creations that were only painted and not drawn by him) or the ghastly Jones deformations, the McKimsons’ waning art is genuinely pleasant to look at, and brought a smile to my face several times.

Actually, just about every page brought a smile to my face. Not purely because of nostalgic recollections of watching the cartoons endlessly on television as a child, or the waves of funny moments with Bugs, Daffy, Sylvester, and Foghorn that still make me laugh today. It’s because the art is mostly just so damned good. There is a proficiency and humbleness to the McKimson wavelength that makes it unwaveringly appealing, the exact thing sorely lacking from so much Hollywood animation in the last half-century. Criticism of McKimson’s direction will never die in animation circles, but ultimately, the man’s biggest crime was having a role in originating the look of some of the most beloved fictional characters ever created, shaping the animation style of the greatest animated films, and turning out a couple dozen really funny cartoons. I don’t think McKimson Jr.’s writing will convert any non-believers, but the presentation of the artwork might convince folks that few classic or modern Hollywood animators have succeeded where McKimson failed. That alone makes the book worth a purchase.

Thanks to historian and voice artist Keith Scott for providing me with some incredible research material that has allowed me to fill in many holes in

Thanks to historian and voice artist Keith Scott for providing me with some incredible research material that has allowed me to fill in many holes in  In the other corner of animation history, there have been many books about the Warner Bros. cartoons as a whole, but few bely the term “vacuous”, and even fewer examine individual figures. Certainly a book about Robert McKimson, a key player in the Termite Terrace legacy, has never been considered, which is why

In the other corner of animation history, there have been many books about the Warner Bros. cartoons as a whole, but few bely the term “vacuous”, and even fewer examine individual figures. Certainly a book about Robert McKimson, a key player in the Termite Terrace legacy, has never been considered, which is why

Whenever the latest one comes out, I always ask myself: how many books on the subject of Disney do we really need?

Whenever the latest one comes out, I always ask myself: how many books on the subject of Disney do we really need?