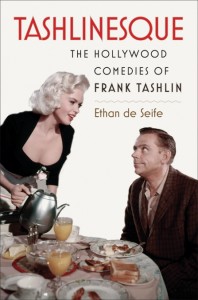

A book on the subject of American filmmaker Frank Tashlin has been vitally needed for decades now. Ethan de Seife has filled that void with his new book, Tashlinesque: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin – somewhat.

A book on the subject of American filmmaker Frank Tashlin has been vitally needed for decades now. Ethan de Seife has filled that void with his new book, Tashlinesque: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin – somewhat.

I’m doubtful de Seife will achieve making Tashlin a more embracing subject. While I have noticed a resurgence of interest in Tashlin’s animated cartoons thanks to the vast majority of them being included on recent DVD compilations (so much so that fans are ranking them on the same level or even higher than esteemed “gods” like Bob Clampett and Chuck Jones), his live-action films being scattershot across so many distributors (and movie stars) ensures no proper home video retrospective. The unjust blemish on the director’s reputation in the guise of Jerry Lewis is also too strong.

Most of those reading my blog are classic animation followers, and if you have zero interest in Tashlin’s work beyond his career in cartooning, skip this book. There’s nothing in it that you’ve never read before, and his coverage of Tashlin’s animation years is largely off the mark.

In trying to dispel the myth that Tashlin did “live-action as cartoons” and “cartoons as live-action” and prove they are really one singular body of work with the same driving ideology, de Seife reveals that he has absolutely no proficiency in dissecting what makes the animated cartoon tick. Story, characterization, humor, and layout are part of any meaningful animation study, to be sure. But so is timing, color stylization, the importance of music, and the actual animation and drawings, none of which are under scrutiny in de Seife’s breakdowns of the select Tashlin cartoons. About the closest he comes to a decent animation study is his analysis of Daffy Duck and the father’s contrast in movement in Nasty Quacks.

Some weird analogies of de Seife’s highlight his lack of knowledge of Warner cartoon history, specifically how Tashlin’s films with Porky Pig and Jayne Mansfield are alike because they both made film stars out of nonentities. Certainly true in the case of Mansfield, but Tashlin was one of several responsible for shaping Porky Pig.

In the black-and-white Looney Tunes of 1936, Tex Avery was the first to turn Porky into a viable leading star, followed by the [rather inept] cartoons by Jack King, and then Tashlin’s. The following year, Avery cast Mel Blanc as Porky and slimmed the character down. Bob Clampett and Chuck Jones polished that design, and a far more appealing and enduring character surfaced than the one in Tashlin’s contemporary cartoons.

Surely Tashlin did some of the best in this period (especially when Blanc started doing the voice in The Case of the Stuttering Pig and Porky’s Double Trouble), but if De Seife was truly scrutinizing the Warner cartoons of the period as he claims to, he’d have drawn the same conclusions regarding the character’s evolution. Instead, his text reads as a willful misinterpretation of the other directors’ cartoons. Because Porky is a more nuanced character in Tashlin’s Porky’s Romance than in King’s Boom, Boom, the earlier films are mostly worthless. Of course, few directors had weaker characterization skills than Jack King in that period. Rather, Tashlin was the first of the directors to repeatedly use Porky as world-weary adult rather than a playful, adventurous one or genuine child.

Surely Tashlin did some of the best in this period (especially when Blanc started doing the voice in The Case of the Stuttering Pig and Porky’s Double Trouble), but if De Seife was truly scrutinizing the Warner cartoons of the period as he claims to, he’d have drawn the same conclusions regarding the character’s evolution. Instead, his text reads as a willful misinterpretation of the other directors’ cartoons. Because Porky is a more nuanced character in Tashlin’s Porky’s Romance than in King’s Boom, Boom, the earlier films are mostly worthless. Of course, few directors had weaker characterization skills than Jack King in that period. Rather, Tashlin was the first of the directors to repeatedly use Porky as world-weary adult rather than a playful, adventurous one or genuine child.

(Curiously, de Seife has nothing to say on Tashlin’s two Bugs Bunny cartoons, the best examples of nailing a difficult animated personality on the first try.)

De Seife also devotes a lot of word space to dissecting the Tashlin and non-Tashlin Warner cartoons in terms of average shot lengths, to illustrate that Tashlin’s cartoons were not all about quick-cutting for humorous effect, but just as well-balanced as the other directors’. Rather than saying this in a simple paragraph, he plugs away many meandering passages with figures and percentages to prove his point. I began wondering if I was reading a mathematical study of 1930s Warner cartoons after awhile.

Devotion to that kind of detail exposes de Seife’s lack of insight into animated film in general. Surely one will have to admit that there are distinct differences between the making of an animated cartoon and a live-action movie, specifically when it comes to the filmmaker’s art/drawing style and how he or she uses it to its fullest potential. De Seife doesn’t even attempt to analyze how that plays into Tashlin’s work.

One thing that makes Tashlin’s Warner cartoons so individualistic is his extensive background in print cartooning. His cartoons consist of stylized animation that just relishes in being drawn, yet still capture the nuances of human behavior and comedy. It made his films the most anti-Disney of the studio’s and kept the dreaded “Illusion of Life” from permeating into them, something even Bob Clampett couldn’t do.

Like Clampett’s cartoons, Tashlin’s were also quite daring in terms of adult content, even more than Avery’s. Whereas Clampett was sophomoric, Tashlin was sophisticated in sexualizing his cartoon’s humor. Tashlin would keep his audience guessing if there was a massive erection in the room, while Clampett would just proudly drop his pants and present it.

Which makes de Seife’s conclusion that Tashlin’s animation is lacking in ‘mature’ content rather puzzling. While there was never anything as blatant as the breasts of a cardboard Jayne Mansfield keeping it from falling on the ground, or a bound, gagged and stripped Shirley MacLaine in a Tashlin Warner cartoon, the seven-minute shorts had their moments of pervy goodness.

I don’t think Bugs Bunny stretching out his ass [beautifully animated by Art Davis] in The Unruly Hare could be interpreted as anything but overtly sexual. Tashlin needlessly calls attention to a woman’s legs and backside in completely arbitrary scenes in Puss n’ Booty and Behind the Meat-Ball. Sometimes there’s even needlessly sexual gags in a carnally off-the-wall picture, as when Daffy takes on Hatta Mari’s musket in Plane Daffy.

I don’t think Bugs Bunny stretching out his ass [beautifully animated by Art Davis] in The Unruly Hare could be interpreted as anything but overtly sexual. Tashlin needlessly calls attention to a woman’s legs and backside in completely arbitrary scenes in Puss n’ Booty and Behind the Meat-Ball. Sometimes there’s even needlessly sexual gags in a carnally off-the-wall picture, as when Daffy takes on Hatta Mari’s musket in Plane Daffy.

If it reads like I’m saying Tashlinesque is a very poor book, it isn’t on the whole, only for most of the first 70 or so pages. Once de Seife gets into Tashlin’s live-action career in the 1950s, the book gets considerably better. (Although he refuses to analyze ‘Tashlinesque’ elements in films Tashlin only wrote and didn’t direct.)

The most interesting passages are when we get a taste of how Tashlin got so much of his lurid material past the Production Code Administration. In short: he acknowledged that the censors wanted changes and responded by simply not making the changes. It’s a wonderfully refreshing change from the endless horror stories that plague many film histories, of how the Code brought down so many great ideas. Here we see a brilliant writer-director putting one after another over the Film Gestapo, like inserting racier dialog in the middle of a long, single shot. When pressed to change it, Tashlin would retort, “It’d be too expensive to reshoot it.” And won.

What I like about de Seife’s analysis of Tashlin’s live-action films is that he rather accurately puts them into context of other comedies of the period, showing that there isn’t anything particularly ‘cartoony’ about them at all. The slapstick in the average Paramount comedy or Columbia short is a continuation of the vaudeville stage, where the impracticality of the gags is solely what makes them funny. This mentality was dominant in most screen comedies of the 1940s with the numerous adaptations of radio personalities. It was a bleak era for genuine comedy classics outside of Preston Sturges, and when you could truly say that the animated shorts were more smartly written than the live-action they were alleged warm-ups to.

What I like about de Seife’s analysis of Tashlin’s live-action films is that he rather accurately puts them into context of other comedies of the period, showing that there isn’t anything particularly ‘cartoony’ about them at all. The slapstick in the average Paramount comedy or Columbia short is a continuation of the vaudeville stage, where the impracticality of the gags is solely what makes them funny. This mentality was dominant in most screen comedies of the 1940s with the numerous adaptations of radio personalities. It was a bleak era for genuine comedy classics outside of Preston Sturges, and when you could truly say that the animated shorts were more smartly written than the live-action they were alleged warm-ups to.

Tashlin and other higher ranked film directors made those gags’ impracticality part of the natural surroundings in their best comedies, thereby making it funnier than typical slapstick. The emphasis in those sight gags was on the fact that the impossible action was treated in a self-aware manner that said, “This is just part of everyday life.” In the 1950s WB tooniverse, it was the difference between Foghorn Leghorn getting blown up by dynamite being funny in itself and Wile E. Coyote’s humiliation and frustration over getting blown up being the humor in the scene.

This contrast became all the more apparent to me when I was watching the DVD collection of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis films that places the two that Tashlin directed among three that he didn’t. While I love Artists and Models beyond reason, this and Hollywood or Bust are not Tashlin’s best, nor Martin’s or Lewis’s best. Yet both perfectly illustrate the difference in the treatment of “cartoony” humor in live-action.

When Sheree North comes out of nowhere to jitterbug with Lewis in the non-Tashlin Living It Up, the energy is funny, but it’s so ham-fisted in its execution that it almost seems out of place in a film centered on mortality. When Shirley MacLaine practically beats the hell out of Lewis while serenading him in Artists, it’s not only uproariously funny, but seems perfectly in tune with life in the Greenwich Village apartment.

Perhaps it’s not the best example. Artists and Models is completely insane overall, but it’s an intelligent insanity. No impracticality is emphasized nor given more prominence over another in any Tashlin film. It’s this steadiness in outlandishness that viewers are responding to in Tashlin’s live-action work; his willful disregard that something is impractical makes it all the more noticeable. When it didn’t work, as is the case in quite a few of his movies with Lewis, the films could be as foppish as any Three Stooges flick. When it did work, as in Son of Paleface and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, you got an American comedy as brilliantly distinctive as anybody’s.

I’m deviating away from de Seife’s book now, but in a good way. His writing on Tashlin’s live-action did what any great critical analysis does: get you thinking more about the filmmaker himself rather than the critic.

The Production Code was losing its teeth in the 1950s and became practically nonexistent in the 1960s. Almost cynically, this is when Tashlin’s comedies began to lose their edge. Many times, writers go out of their way to not acknowledge that a director’s work got considerably weaker later (see many essays/books on Alfred Hitchcock or Billy Wilder). Fortunately, de Seife doesn’t do that, and goes into splendid detail about Tashlin’s undeniable decline in the 1960s, bringing up the crucial point that he may have been negatively affected by collaborating with Jerry Lewis.

There can be no doubt about this. Lewis’s egotism and penchant for sap taints a great deal of Tashlin’s 1960s work, even when Lewis wasn’t involved. It explains how Tashlin managed to work with such a mismatch as Doris Day in his later films. To Tashlin’s credit, however, outside of Tashlin, Billy Wilder, and Blake Edwards, no one in American film even attempted doing something remotely interesting with comedy in the early 1960s. It was a dismal era when every comedy was shot like a color sitcom and was just as well-directed – an appraisal that can fortunately never be applied to any of Tashlin’s work.

There can be no doubt about this. Lewis’s egotism and penchant for sap taints a great deal of Tashlin’s 1960s work, even when Lewis wasn’t involved. It explains how Tashlin managed to work with such a mismatch as Doris Day in his later films. To Tashlin’s credit, however, outside of Tashlin, Billy Wilder, and Blake Edwards, no one in American film even attempted doing something remotely interesting with comedy in the early 1960s. It was a dismal era when every comedy was shot like a color sitcom and was just as well-directed – an appraisal that can fortunately never be applied to any of Tashlin’s work.

Tashlinesque provides much needed scholarly prose about Frank Tashlin, but its fundamental misconception of animation does a disservice to a very important part of the director’s body of work. What’s needed now is a truly comprehensive look at Tashlin by a writer that understands both animation and live-action, and can intelligently write about the man’s work in each medium. Maybe Jaime Weinman should write it. Or me.