I’ve written a lot about Famous Studios and have been resisting writing this review for some time. Partly because I was so involved in this release that it’s somewhat repugnant to look at it again with a critical eye, partly because you can only say so much about Famous without getting as repetitious as their cartoons’ reputation.

I’ve written a lot about Famous Studios and have been resisting writing this review for some time. Partly because I was so involved in this release that it’s somewhat repugnant to look at it again with a critical eye, partly because you can only say so much about Famous without getting as repetitious as their cartoons’ reputation.

(Full disclosure: I provided many elements for this release, as well as two audio commentaries. I highly recommend you don’t listen to them.)

Absolutely irredeemable artists and filmmakers have gotten substantial coverage in the form of heavy tomes, but very few animation historians and writers have gone beyond the Disney-WB-MGM trifecta of Golden Age animation. The best animators and directors blossomed there, so it’s no surprise that attention deviates towards them. It’s just dreadful that information on the second and third-tier studios hasn’t seen print when you can get in-depth tales of absolute garbage live-action films of the same period.

Animation writers seem to have a hard time committing to long-term ambitious projects (I know I do). The real Walter Lantz story is still waiting to be told. You know that the tale of an independent and increasingly prudish studio owner whose star character had the most pornographic name of any has to be interesting, based on that fact alone (never mind who he employed. Ditto for the real Fleischer story. The ideal author of that particular book fears a lack of pictures/art would hurt sales and make the venture unworthy of his time, but given the pedestrian coverage just about every author has given the historic studio, I’ll take the text over visual aides any day.

*****

Famous Studios is treated by most as the Fleischers’ retarded stepchild, but both are essentially the same outfit. The Fleischer Studio became Paramount’s own well before the brothers were ousted. They were also getting fairly pedestrian before the name change too.

This may be a controversial stance, but the problems most people associate with Famous Studios have strong roots in the Fleischers’ Golden Age in the 1930s. There is no disputing the entertainment value of their best cartoons’, nor the important pioneering done in their halls. But there is zero consistency in the actual films through the whole decade. They either were completely ignorant of what made their best cartoons unbeatable or too inept to follow up on them. Say what you will about Shamus Culhane, but he was there and had a point (and did some amazing work elsewhere that backed up his argument).

The Talkartoons range from unparalleled brilliance to as crude as anything else being done in New York. Popeye might have been the first original personality in animation in years (the very first being Felix the Cat), but while the Fleischers were doing those shorts, they also did their worst and dullest Betty Boops. Disney ironed out its clunkier techniques as the decade closed, yet there’s still some seriously bad drawing and animation scattered through all of the Fleischer output, even in the features.

The Fleischer Studio was a NY equivalent of the Schlesinger and Warner studios: guys who just wanted to have a good time while sticking it to Disney and doing things against the status quo. But the Fleischers had no sense of focus, management, or long-term vision. The very fact that they refused to give a proper credit to the people who actually did most of the directorial duties on the cartoons makes it plain there was no chance of a Chuck Jones or Bob Clampett rising through the ranks. The system at Fleischer was just different from West Coast studios and was not designed to permit it. Famous merely followed a well-established methodology.

*****

Steve Stanchfield’s Noveltoons Original Classics highlights the 1944-1950 period at Famous. One thing that’s going to startle any viewer is how sharp and colorful the majority of the cartoons look when taken from original 35mm IB Technicolor prints. This is Looney Tunes Golden Collection and Disney Treasures level with much lesser elements, yielding similar, eye-popping results.

Steve Stanchfield’s Noveltoons Original Classics highlights the 1944-1950 period at Famous. One thing that’s going to startle any viewer is how sharp and colorful the majority of the cartoons look when taken from original 35mm IB Technicolor prints. This is Looney Tunes Golden Collection and Disney Treasures level with much lesser elements, yielding similar, eye-popping results.

The compilation gives a perfect summation of the studio: uneven, but endearingly uneven. If there’s one thing to recommend about them, they’re Golden Age animation’s middleman. You will not find cartoons well-defined as the best of Warners and MGM, or as feisty and inventive as the cream of Fleischer the previous decade. But you won’t find things as routinely aimless as Terry, Screen Gems, or, yes, Disney cartoons of the same period. That might be part of the reason for the Famous stigma – they can be too ordinary to be worthy of real attention.

If there’s a mark in Famous’s favor, they are an improvement over the last few years of the Fleischer studio, when a descension into hell was inevitable. In their resistance of the Disney influence, the Fleischers unwisely eschewed almost everything to do with the West Coast; most prominently, easier-to-animate and appealing character designs, costing them future winning personalities and success. As the Noveltoons disc begins, you’ll see a strange hybrid between the established Fleischer and later Famous style. Any number of characters in Cilly Goose or Scrappily Married would be right at home in a Fleischer Color Classic. In the case of the hopelessly lame Yankee Doodle Donkey, Spunky is a Fleischer design awkwardly morphed into something more animatable.

If there’s a mark in Famous’s favor, they are an improvement over the last few years of the Fleischer studio, when a descension into hell was inevitable. In their resistance of the Disney influence, the Fleischers unwisely eschewed almost everything to do with the West Coast; most prominently, easier-to-animate and appealing character designs, costing them future winning personalities and success. As the Noveltoons disc begins, you’ll see a strange hybrid between the established Fleischer and later Famous style. Any number of characters in Cilly Goose or Scrappily Married would be right at home in a Fleischer Color Classic. In the case of the hopelessly lame Yankee Doodle Donkey, Spunky is a Fleischer design awkwardly morphed into something more animatable.

Coherent structure was a foreign element to most Fleischer product, save the Popeyes, so getting into a groove of making cartoons that could compete with the typical 1940s rowdiness took a few years at Famous, making all of their attempts at such seem regressive. It’s a shame, because there is actually some comedic originality scattered throughout the set. Blackie the Lamb is highly reminiscent of Bugs Bunny, yet there’s a whole “close your eyes and count to ten” routine in A Lamb in a Jam that predates the rabbit’s use of it by a whole year. There are cat-and-mice pictures, mostly featuring Herman the Mouse, that are at least as well-animated and funny as the better Tom & Jerrys. One of the studio’s best cartoons, Jim Tyer’s fiendish Cheese Burglar, had its concept reworked by Friz Freleng years later [brilliantly] into Stooge for a Mouse.

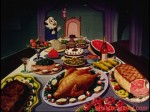

The execution of scenes and attempts at acting in many of the cartoons hint at high ambition. It’s strongest in something like Sudden Fried Chicken, an excellent cartoon that can hold its own against the plethora of outrageously funny cartoons being made in Hollywood in 1946. Unfortunately, the Fleischer/Famous system was built to keep anyone from fully utilizing it. Willard Bowsky came closer to “auteur” status than anyone else at the studio in the 1930s, but he was an exception.

The execution of scenes and attempts at acting in many of the cartoons hint at high ambition. It’s strongest in something like Sudden Fried Chicken, an excellent cartoon that can hold its own against the plethora of outrageously funny cartoons being made in Hollywood in 1946. Unfortunately, the Fleischer/Famous system was built to keep anyone from fully utilizing it. Willard Bowsky came closer to “auteur” status than anyone else at the studio in the 1930s, but he was an exception.

One can also almost sense genuine direction at Famous coming from Bill Tytla (who proved that being the greatest animator of all-time may not make you a good director). Not just in the draftsmanship (thanks the powerhouse team of George Germanetti and Steve Muffatti), but shorts like The Wee Men and The Bored Cuckoo are clearly attempts by Tytla to capsulize Disney feature material into a much shorter length and hesitant format. Perhaps if Tytla made the cartoons look like a five year-old drew them, Famous would get accolades for being revolutionary by merely putting a facelift on retrograde stories.

*****

It goes without saying that this set exemplifies the difference between “great animation” and “great character animation”. Due to the lack of strong direction, there is an incredible amount of the former at Famous, but very little of the latter. This isn’t a problem exclusive to Famous, though, as truly great, perfectly-realized work is rare in any medium.

What’s interesting is that the potential for that kind of character animation was very much visible throughout the history of Famous. The two animators whose work was always clearly better-phrased and acted than their contemporaries were John Gentilella (Johnny Gent) and Marty Taras. Their set-ups are so intricate, their lip-sync and timing so precise, that it’s amazing they weren’t taking instruction from strong directors.

What’s interesting is that the potential for that kind of character animation was very much visible throughout the history of Famous. The two animators whose work was always clearly better-phrased and acted than their contemporaries were John Gentilella (Johnny Gent) and Marty Taras. Their set-ups are so intricate, their lip-sync and timing so precise, that it’s amazing they weren’t taking instruction from strong directors.

Taras created Baby Huey (and was also the model for him), and it’s his scene in Quack-a-Doodle Doo where Huey meets the fox for the first time that perfectly (and rather creepily) establishes that the lummox can’t be killed through broad, detailed, and funny animation.

Gent is underrepresented on this collection, as is Jim Tyer (whose significance needs no explanation), but that’s through no fault of Stanchfield’s programming; their work was largely confined to the Popeye series. A Lamb in a Jam is a bit of a gem because we get to see Gent handle funny animals rather than Homo sapiens. The best scene of Gent’s is at the end, with Wolfie struggling to count to ten. Gent’s handling makes the character believably pathetic as he strives to get past six. The scene is almost “Disney-like” in its fluidity and articulation, but with none of the over-direction or artificialness associated with that term. It’s also incredibly funny, capping off with Wolfie’s overzealous “TEN!”

Gent is underrepresented on this collection, as is Jim Tyer (whose significance needs no explanation), but that’s through no fault of Stanchfield’s programming; their work was largely confined to the Popeye series. A Lamb in a Jam is a bit of a gem because we get to see Gent handle funny animals rather than Homo sapiens. The best scene of Gent’s is at the end, with Wolfie struggling to count to ten. Gent’s handling makes the character believably pathetic as he strives to get past six. The scene is almost “Disney-like” in its fluidity and articulation, but with none of the over-direction or artificialness associated with that term. It’s also incredibly funny, capping off with Wolfie’s overzealous “TEN!”

A cursory view of the set makes it easy to envision not just these two, but any number of animators and draftsmen at Famous becoming more renowned had they had the fortune of working with a strong director. (The closest chance most of them got was with Ralph Bakshi, when they were all past their prime.)

By the time of Saved By the Bell (the last cartoon, chronologically, in the NTA-Republic package), the seeds for the “Harveytoon” era were well in place, and the kind of film that could take advantage of an animator like Taras or Gent became nonexistent. From approximately 1951-1955, it almost seemed against company policy to stray from the “opening, 3 gags, and closing” format. (When a short in this era tried to stray, like the minor Dave Tendlar-Taras masterpiece Kitty Cornered, it really stood out.) The animation was fine, if not formulaic, but the content could get so taxing it belied any expertise otherwise.

Jerry Beck mentions in one of his audio commentaries that this problem stems from Seymour Kneitel and Izzy Sparber adhering to a literal timing guide as a “bible” (see this important historical document posted by Ginny Mahoney, Kneitel’s daughter, here and here). Surviving boards (one for Quack-a-Doodle-Doo is included in the bonus features) are indeed lively and funny, only proving how much can change over the course of the production of an animated short. Not much has changed today.

This collection didn’t give me a deeper appreciation for Famous Studios, and I doubt it will change anyone ele’s predispositions, but Stanchfield’s herculean effort in presenting these cartoons properly (which hasn’t happened since their original release) will make others more susceptible to understanding why the “also-rans” are worthy of proper coverage and preservation (as he’s done chronicling the near entirety of the Van Beuren catalog). I think anyone working towards that goal should be commended and is deserving of our full support. Who knows, you might actually laugh at one of these cartoons too.