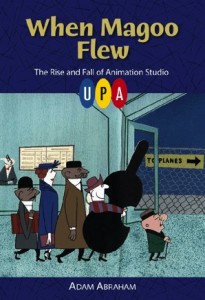

Adam Abraham’s When Magoo Flew: The Rise and Fall of Animation Studio UPA takes on the unenviable task of chronicling United Productions of America, the most raved about but least known about studio of the Golden Age of animation. In general, he succeeds at making this a key text, the go-to-book for anyone seeking information on the studio.

Adam Abraham’s When Magoo Flew: The Rise and Fall of Animation Studio UPA takes on the unenviable task of chronicling United Productions of America, the most raved about but least known about studio of the Golden Age of animation. In general, he succeeds at making this a key text, the go-to-book for anyone seeking information on the studio.

Like Mike Barrier, Abraham actually uses solid end notes, so you’re able to see where the information came from. You’d be surprised how rare this is in animation books; some document or long-dead person is typically quoted without citation or context. Abraham’s thorough use of solid research and colorful anecdotes with extensive citations makes his book worth purchasing for this alone.

Some of the usual problems with animation texts do arise in Abraham’s book. Displaced chronology is inevitable in an animation history, so leeway should be allotted, especially when Abraham has gone to such great lengths in his research. But he could have still been clearer in many cases. He spends a great deal of time talking about Bobe Cannon as a director before his most excellent “Red Scare” chapter, but he discusses films made both before and after John Hubley’s firing [related to his HUAC-offending activities]. While writing about the studio’s early 1950s triumphs, he does not discuss Unicorn in the Garden and I was left puzzled by its absence. Abraham discusses the film later, in a chapter about Mr. Magoo: 1001 Arabian Nights, while chronicling the studio’s various feature film projects (Unicorn was intended to be part of a James Thurber feature).

Sometimes the displaced chronology works very poorly. The most distinct example is Abraham choosing to discuss Chuck Jones’s The Dover Boys after John Hubley’s time at Screen Gems, so we get a sentence that reads “The Dover Boys resembles The Rocky Road to Ruin“. That exact wording, of course, shouldn’t exist in any language, regardless of context.

What I also noticed is a strong commitment to academia in Abraham’s book, and a relying on the UPA personnel’s feelings and opinions in order to avoid taking and stating a position himself. Some of those positions are strong (pro-UPA, as to be expected), many others (the negative) are weak. This of course allows him to avoid telling you that a large part of the UPA output after Hubley left never met those high standards again. (A most notable exception is his reprinting the priceless and devastating results of a focus testing of The Gerald McBoing Boing Show in its entirety.) It’s also especially evident in earlier grating passages, with the prevailing viewpoint that Disney and Warner artists (particularly the wonderful Frank Tashlin) were aware of the role modern art and graphics could play in animation, but they were either too stupid or indifferent to follow through.

Studio brickbats are covered well, the “Red Scare” chapter chronicling the attempted purging of UPA and the departure of John Hubley being the best example. It’s also one of the few places Abraham takes a strong position himself – that the McCarthy era was one of the most terrifying and shameful periods in American history – because it’s the only reasonable position that can be taken.

Other moments of conflict aren’t done the justice Barrier did them in Hollywood Cartoons with shorter word space. Producer Steve Bosustow hated Unicorn in the Garden and that’s exactly why Bill Hurtz (the film’s director) left UPA the second Shamus Culhane (who is introduced in the text unceremoniously) asked him to. We never sense that in Abraham’s book, because he never tells us in plain terms and the chronology is all over the place. Hurtz leaves UPA in chapter eight but he’s still there in chapter nine.

There was also a real missed opportunity in not using Bill Scott as a figure thoroughly, for his recollections are revealing of the elevation of design and the minimizing of everything else in the animation process during this era. UPA housed Bullwinkle J. Moose, about as strong an antithesis of the UPA style I can think of, as one of its main writers. Such a section writes itself, but Scott is pushed to the sidelines.

That emphasis on design over animation and the establishment of UPA are, without a doubt, a product of modernism permeating through American culture. Kirk Nachman took me to task in the comments of my previous post for not mentioning that. I agree, but there’s only so much you can do with an article before you bore the reader. There’s only so much you can do with a book too, but if such a dissection has a place, it’s in a history of UPA, and I wish Abraham attempted adding that dimension to his book. For as important as he wants us to believe UPA and its artists are, they’re still confined to the animation ghetto in this book, rather than how they fit into the larger picture of art and film in the mid-twentieth century.

Regardless, Abraham ultimately did as excellent a job possible of making the UPA story readable. About the only truly boring part was a chapter on advertising. The text did nothing to make UPA’s commercials seem any more noteworthy that anyone else’s [Were they proven more effective than the competition’s, I wonder?] and only reminded me that commercials are not films in any way, shape or form. The chapter serves its purpose of putting the information out there (and it’s quite necessary, given how much work in advertising UPA did), but it did nothing to pique my curiosity.When Magoo Flew is light but not lightweight. Abraham doesn’t go out of his way to use words that no one would ever actually use in real life. I learned a lot I didn’t know, and many of my favorite artists became real people in a way they never have been before. Some animator identifications were intriguing, either coming from studio drafts or the unerring Mike Kazaleh. The book serves as a decent, if not perfect, model for any enterprising writers who want to write about other neglected animation studios. People may whine about how it’s too late for proper histories of those places to be written, given how most of animation’s forefathers and early worker bees are all dead, but Abraham proves this obstacle can be overcome.

He also, however, reaffirmed my own skepticism towards the UPA studio, style and films rather than give me new appreciation for them, but for that I can’t fault it. Reading it was too educational an experience. And hey, his chapter on Mr. Magoo has gotten me excited about seeing those cartoons again on the forthcoming DVD release. It’s an important book, and if you have any interest in American animation history, you should buy this, and the just released Jolly Frolics collection, without any reservations.

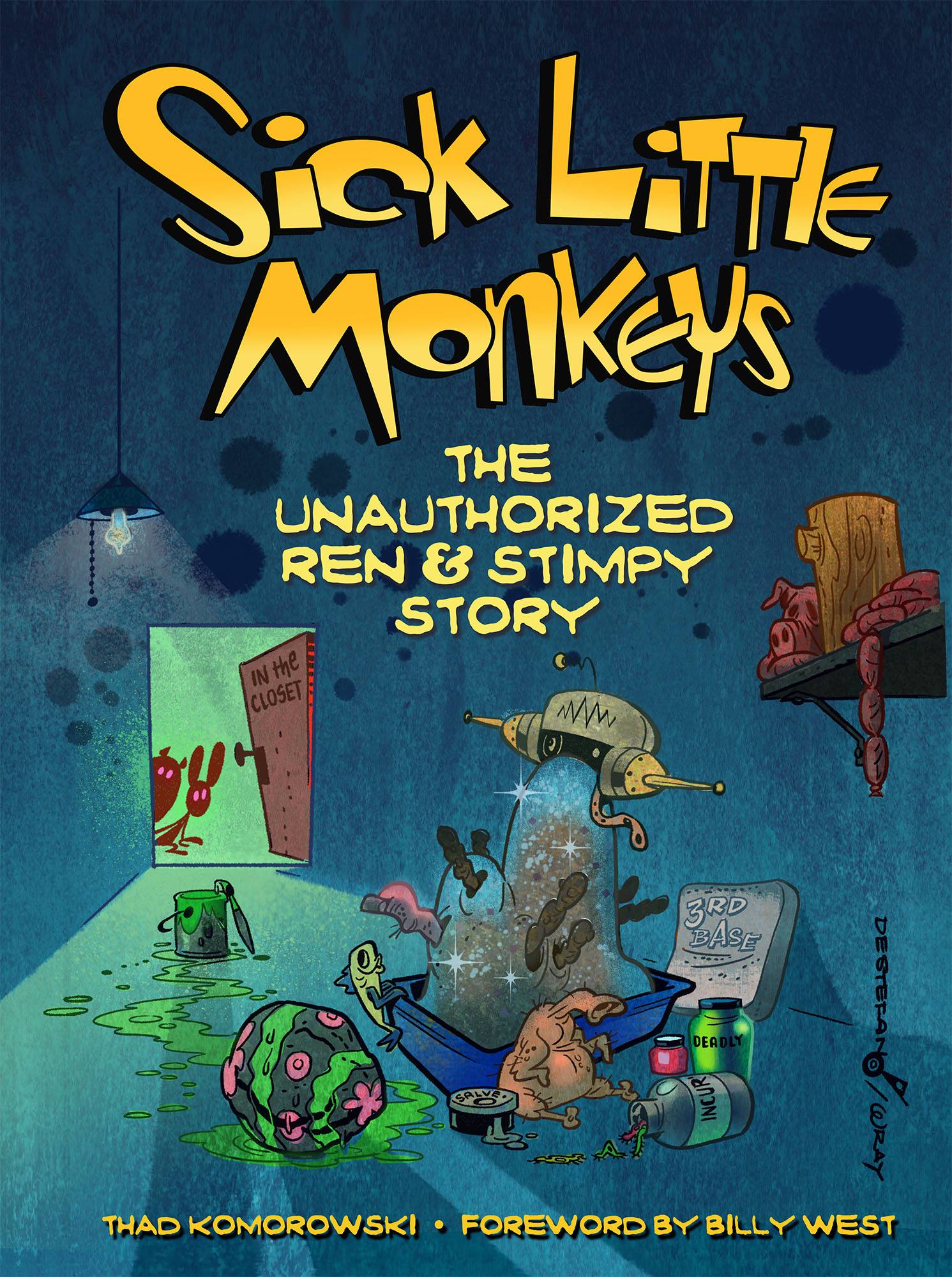

This is an absolutely excellent review, Thad. I was also bothered by the out of sequence chronology, but gave Abraham a pass on it. He did, after all, cover a lot of material not seen before. Of course, you were right to bring it up.

Thanks, Michael. The complete lack of comments on this post made me wonder if anyone had actually read it. Knowing you enjoyed it makes it worth it.

Interesting review, I don’t really care for Abraham’s seemingly strong bias towards UPA in just the few notes you mentioned, especially the matter of “others were just too stupid or indifferent to adopt a highly experimental animation style.”

Please note that that is only my interpretation of Adam Abraham’s opinion and he did not actually write those words. He and I had a few friendly e-mal exchanges several weeks ago and he appreciated my review.